Maumee Bay State Park is one of Ohio’s most popular tourist spots drawing hundreds of thousands of visitors a year. But long before this Lake Erie shoreline attraction became a summertime mecca for swimmers, campers and golfers, it was reported to be the site of a stunning archaeological discovery. In 1895, on October 24th, it was widely reported in many newspapers throughout the country that a prehistoric Indian mound was found on the site which was known as the Niles Farm at the time, owned by well known writer and lawyer, Henry Thayer Niles.

Inside the mound, about 12 feet below the surface, 20 skeletons were found in a “sitting posture” and near each skeleton was a curious piece of pottery, “different from other mounds in other localities”. The skeletons, however were said to have crumbled upon exposure to air and “fell to dust”. However it was reported that two skulls were recovered and stayed intact. They measured about the same size as a normal human skull, but had much larger, heavier and stronger jawbones”. It was also reported that the niece of Henry Thayer, Niles who was a student of ancient cultures was there for the excavation, along with her uncle Henry. The newspaper wire accounts say each skeleton’s face was turned toward the east. And estimated that each bowl of pottery would hold about a gallon of fluid and that the edges of the bowls were “fluted” or “crimped” unlike most pottery of this type. The pottery also had pictographs or hieroglyphic type images on its sides. The age of the remains and mound were unknown, but Henry Nile’s niece estimated that they could have been several thousand years old. As to what other excavations may have followed on the Niles property, if any, is an unknown, as well as the eventual whereabouts of the pottery, the skulls and other artifacts that were unearthed that day. Such discoveries of earlier civilization in the Black Swamp during the 1800’s were not uncommon. Less than a year later in 1896, a similar revelation was made when several “ancient Indian” skeletons were recovered from an earthen mound in what used to be the Ironville neighborhood of East Toledo, roughly located in the area of Millard and Front Streets. That particular area was said by early settlers to be inhabited by several Indian settlements along the riverfront at Maumee Bay. However, what relationship those “ancient” burial sites might have had to the latter day Native Americans living in the area in the 1800’s is unknown.

It’s believed that in Lucas County alone there were as many as a dozen “ancient” sites. Perhaps more. Sadly though, most of them are invisible to us today. Assigned to obscure newspaper articles, diaries of pioneers or the conjecture of researchers. Most of the locations in the Toledo area that were discovered were never excavated with any scientific method, so as a result, we know relatively little about them or where they were. The only place that is officially marked, noting the existence of these ancient people, is found on Miami Street in East Toledo where the city’s earliest settlers found a large earthworks of an aboriginal fort situated atop the banks overlooking the narrow bend in the Maumee river. The fort was likely placed there strategically so that the ancient inhabitants could detect any movement from any potential adversaries on the river in both directions. Those earthworks and artifacts, however, were likely obliterated by the ambitions of a hungry plow. As the new residents of the 1830’s and 40’s were eager to work the soil and get crops in the ground, they were likely unconcerned with such historical curiosities in the course of their labor.

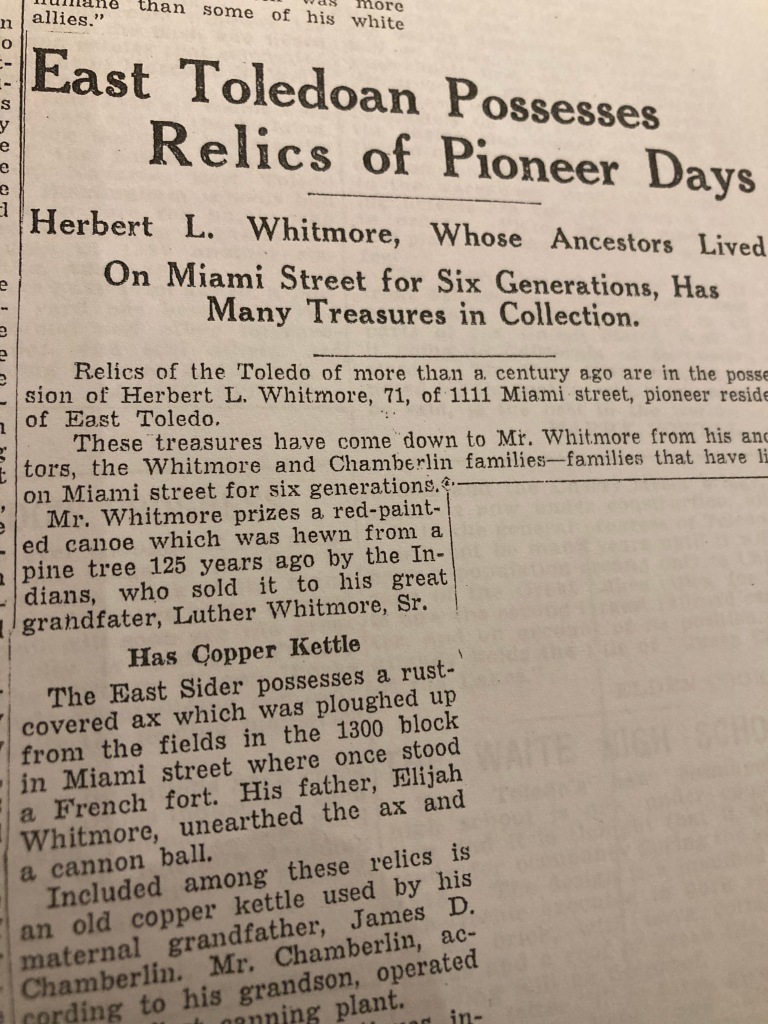

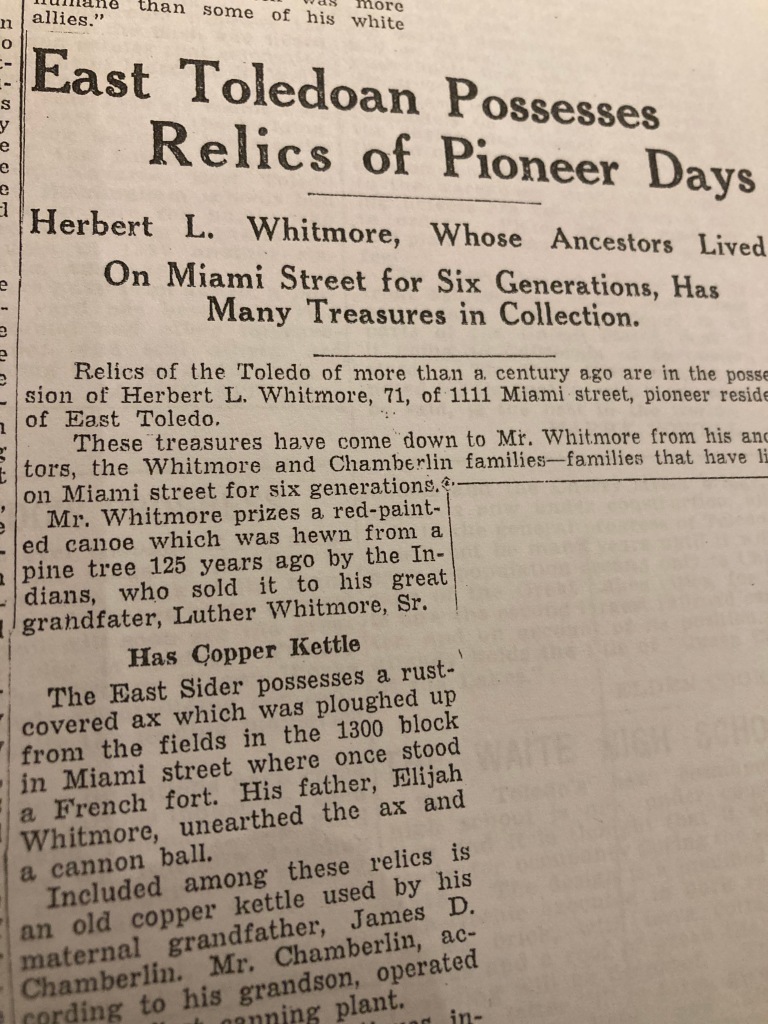

An article from the Toledo Blade in the 1930’s, featured an interview with the Herbert Whitmore, who was a descendant of one of the original pioneer families who settled along that area of the Maumee River. It was noted in the story that the family still had several artifacts taken from the fort site as the early settlers tilled the land for farming. Pots, arrowheads and even a French Axe was found as it was believed that the early French explorers in the 1700’s may have made camp at the site, long before the first pioneers from the East came to make it their home. At this time, a stone marker, is the only thing that denotes the prehistoric fort’s existence. It was placed there in the early 1940’s by the Daughters of the American Revolution.

Today, it remains as a mere roadside curiosity dwarfed by the grain elevators that tower above it and discolored by the exhaust of the cars and trucks that speed past it. For what it’s worth: A street adjacent to the marker was even named Fort Street at one time, but even that has been changed. it is now Hathaway Street. So time moves on. As time moved on into the 1970’s, the desire by the state of Ohio to build a new state park on the area known as the Niles Farm in Eastern Lucas County was turning from talk to action.

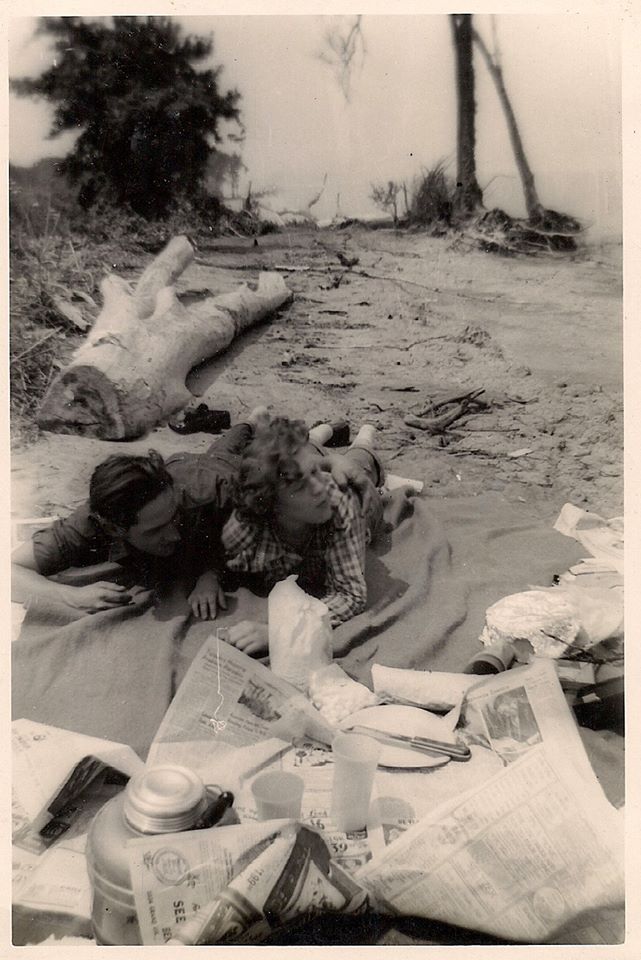

Long after the Niles family owned the land and operated a farm there, much of the lakeshore property had become a “resort” areas with summer cottages and a popular place for Toledo families from the 1920’s to the 1960’s to use the small stretch of beach as a summer playground on the lake. A massive storm and flood destroyed many of the little cottages in the fall of 1972.

By 1975, the land of the old Niles Farm was sold to the state and was even called a state park in advent of the project. One of the studies undertaken to determine what impact such an endeavor would have on this fragile wetlands environment along the lake was an archaeological evaluation. It involved some limited excavations in the sand bermed area known as Niles Beach. Roughly, just east of where the current state park lodge is located. The report from 1981 on the historical importance of the area was conducted by a team of well known and respected archaeologists. It included Dr. Michael Pratt, a familiar name in Northwest Ohio for other historic investigations he has conducted throughout the area. This particular survey of the old Niles Farm and the heavily wooded beach area did turn up a variety of artifacts of ancient peoples. Almost 90 in all. Some ceramic, such as ceramic pottery or sherds, and some made of stone, such as grinding tools, points and flakes from chert or flint. It was also noted that hundreds of artifacts had already been taken and removed from the site by a man named Eugene Paulsen of nearby Genoa. He told the investigators that he probably removed over 200 pieces of pottery and other lithic or stone items that he found embedded in the clay or washed ashore near the beach. What happened to those artifacts that were accumulated by Mr. Paulsen are unknown.

The final report said all of the artifacts found at the site in the 1981 search were probably from 1300 to 1500 A.D and were from the late Woodland people. Of the other artifacts found by other collectors – those artifacts represented every culture from the Paleo Indian through the modern day “Indians” of the 1800’s.. Missing from their report was the story of the 1895 burial mound that was unearthed with the 20 skeletons inside. That historical event was never mentioned, by ignorance of it, or design. Not sure. It did say that earlier artifact discovery sites were now obscured by the rising lake levels which had essentially puts hundreds of feet of historic shoreline underwater. The researchers concluded that the Niles Farm and Beach site had such little historical significance that it would not need to be put on the National Historic Register and should not impact the building of a park. Within a few years, the bulldozers and earth moving equipment began carving up the old Niles Farm into a plat of roadways, parking lots, campsites, a lodge and cabins and a golf course. And Maumee State Park is now a reality. One can only wonder what or whom may be buried beneath.