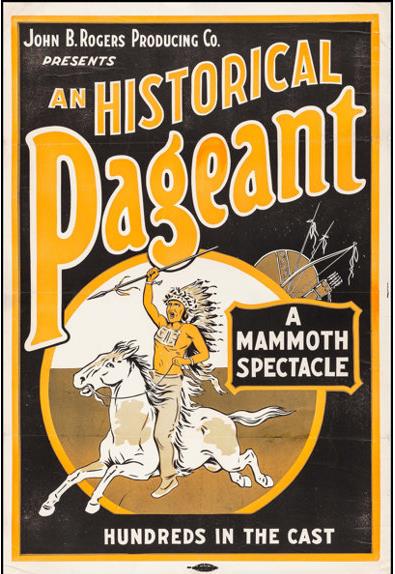

It hardly seems likely, but there was once a modest little red brick building on Center Street in Fostoria Ohio that put more people under the lights of the stage and theater than probably any other drama producers this side of Broadway. From coast-to-coast, for most of the 1900’s, thousands of communities, large and small, would become seduced by the bright lights and the scriptwriters from this Fostoria company who helped those regular folks put on the grease paint and costumes so they could “put on a play”. Not just any typical community theater production, but grand outdoor pageants designed to highlight the histories of those communities that were celebrating centennials, or other significant milestones of their heritage.

The company was the John B. Rogers Company, started in 1903, by Mr. John Rogers, an attorney from Fostoria who used the various talents of local actors and musicians to stage his own local dramas and musicals. Enjoying early success, Rogers soon expanded the concept and began employing the talents and eagerness of other amateurs in other communities to celebrate the anniversaries and centennials. Many of the early productions were performed on indoor stages as operas, or minstrel shows. As the years progressed the company began selling community leaders on the idea of staging elaborate Centennial anniversaries, or commemorations of notable events of history from their area.

The shows would often utilize a cast of hundreds of people, a truckload of period costumes, various animals, a large rolling stock of wagon and cars, plus a wealth of music scores, and about a dozen choreographed dance routines. In later years, the Rogers’ directors included early forms of multi media complete with slide shows, sound effects and pyrotechnics. Most of these elaborate shows were performed on a hand-crafted grand stage, made of platforms, scaffolding and curtains about 200 feet in length. It was built strategically on a football field where thousands of people attended the spectaculars from the stands.

These pageants were usually the culmination of a year-long celebration of the centennial or the sesqui-centennial at a 150 years. After World War Two, company officials estimated the Rogers’ Company produced over 5,000 of these shows before they finally closed down operations in 1977 in Fostoria, however another company bought the Rogers inventory and moved it to the Pittsburgh area where it continued until the 1980’s.

The Rogers company, on average, would produce about 70 shows a summer. Most of operations focused on small town America where local communities would pay a fee for the Rogers company to design a celebration plan for them, that included not just an outdoor historical pageant, but would also give them an organization “plan of action” with which the townspeople could use to stage the entire year-long celebration. Those festivities always included beard contests, vintage clothing sales, commemorative dinner plates, historical programs and photos, wooden nickels, and other souvenirs of the community’s celebration. In the final six weeks of the event, the company would assign a director-business manager to the town to direct the pageant and generally oversee the celebration to ensure that company procedures and fiscal policies were being followed.

This writer became very familiar with the Rogers Company when I went to work for them in the summer of 1969, as a wet-behind-the-ears 20-year-old freshly minted “director”. Yes, I was unusually young for this type of heady assignment, but not one to shrink from adventure. One spring morning, I flew to points south to begin my director’s training in the small southern community of Clayton North Carolina, a few miles south of Raleigh.

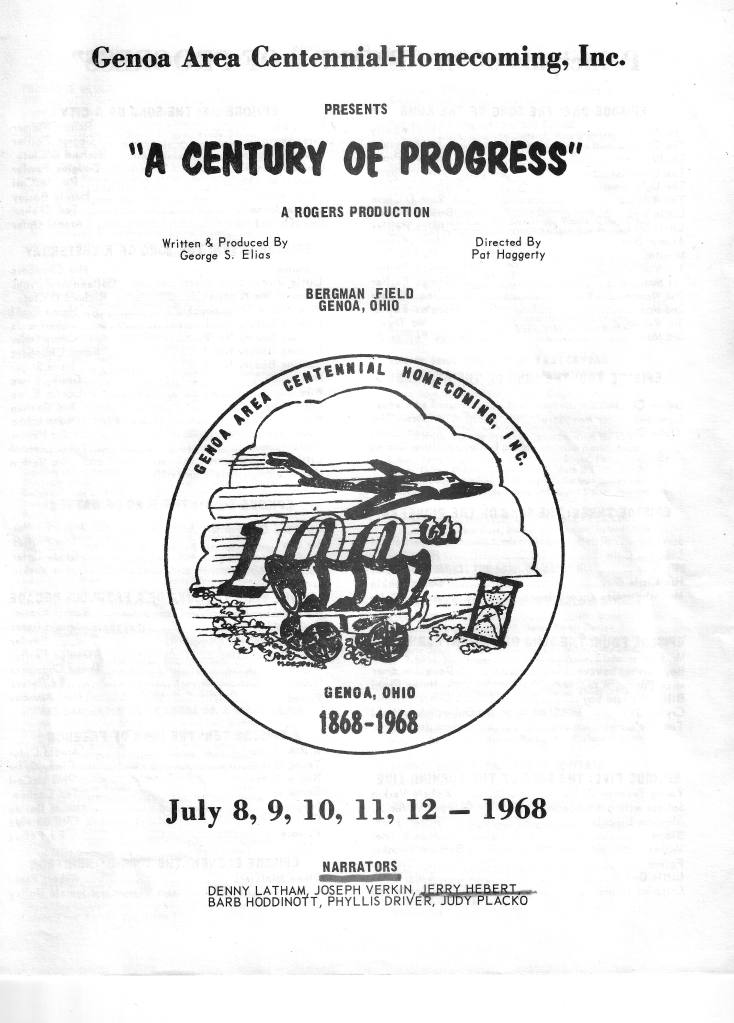

(My first association with Rogers came the summer before when I took part in their production of Genoa Ohio’s centennial pageant in 1968. I was a theater major at the time, and the chance to work for Rogers the next summer was an experience of a lifetime)

Because this story was intended to be about the Rogers’ Company, and not about me, I’ll try to refrain from too much self-indulgence, but I will attempt to provide a unique perspective of the company and the effect in had on the communities they worked with.

The Clayton show was special and somewhat atypical because it was being directed by the Vice President of the company, George S. Elias. A man as unforgettable as he was skilled at his craft. With hundreds of Rogers shows on his long lists of credits, George also brought to his mini-school of new directors, an unflinching passion for the world of show business and showmanship. His stocky build,his soft blue eyes, and a face framed by a shock of graying blond hair, combined with a friendly smile and quick wit, had little trouble getting the attention of those around him. Be they young directors, novice actors or the most influential community’s leaders. I was fortunate to have had George Elias as a mentor in those early years.

George’s proudest accomplishment as a Rogers’ director was no doubt his annual reenactment of Custer’s Last Stand at the Crow Indian Reservation in Montana. It was a brilliant idea designed to raise money every year for the reservation and to tell the story of this great American story from the perspective of the Indians who crushed Custer’s 7th Calvary unit.

Elias for a number of years wrote and directed the spectacular battle scene, in classic Cecil B. DeMille’s style with bull-horn in hand, directing the hundreds of actors on horses with guns and arrows to be brutal and violent, while at the same time imploring them not to hurt anyone. Elias became so loved by the Crow Nation, he was made an honorary tribe member. By 1969, Elias was on set with director Arthur Penn, offering technical advice in the production of the movie “Little Big Man” with Dustin Hoffman and Faye Dunaway. Elias called me in June of 1969 to ask if I wanted to come out for the weekend to see the battle scenes being shot and to meet with Penn and the crew. I declined. A decision I have always regretted.

George Elias was not the only Rogers’ director whose roots were buried deep in the loam of Hollywood and Broadway. There were many others, including screen writers, dancers, actors, and behind the scenes technicians, who joined this Fostoria company during the summer months to earn some extra money and to experience a rich slice of pure Americana. One of the most popular directors for the company during its last years in operation was Carl Hawley, a Hollywood scriptwriter and showman who delighted in lending his experience and talents to these small town productions.

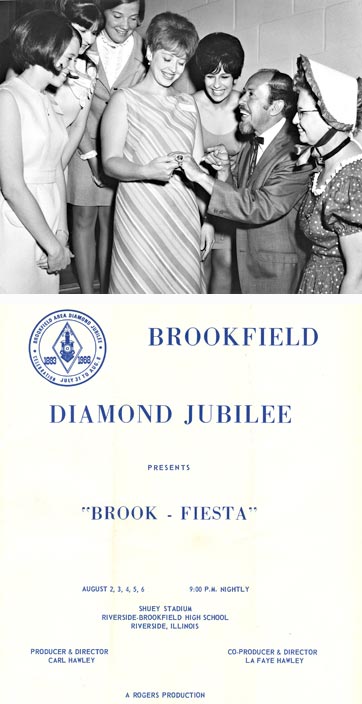

In 1968, Hawley and his wife LaFaye, produced a show for Brookfield, Illinois’s 75th anniversary, called the Diamond Jubilee. The local paper wrote of Hawley.

Everything was coming together. In late June “congenial” Carl Hawley, of Hollywood, Calif., arrived in Brookfield to produce and direct the pageant. Apparently no local person could come up to the standards needed for this job, so Hawley was sent for by the Rogers Company.

Hawley was a true showman, in the best “S.E. Gross” style, brimming over with good nature, optimism and a fine sense of flamboyance. And he had 20 years’ worth of experience in promoting such spectaculars as this.

The July 3rd Enterprise reported that “he has worked with a number of movie stars before joining the Rogers Company. He has assisted in producing and directing James Arness in ‘Gunsmoke,’ Red Skelton and others. He has also traveled with Bing Crosby and appeared in movies under the name Carlos Fernando.”

On his pinky finger, Hawley wore an outrageously large ring, with a gigantic diamond in it that would’ve made Eva Gabor jealous, if it were real. He wore it, he said, as a symbol of Brookfield’s Diamond Jubilee. In early July, his wife, LaFaye, arrived to help co-produce and direct.

There were many directors in the history of the Rogers company and they essentially became the public face of this mostly obscure Northwest Ohio company that provided a wealth of memories to hundreds of thousands of people across the nation. One of their long time directors, Phillys Shelflow, left her Hollywood home each year along with her husband to direct and choreograph the pageants. She said in a 1968 interview that she loved the work because it was all about “bringing America to Americans”.

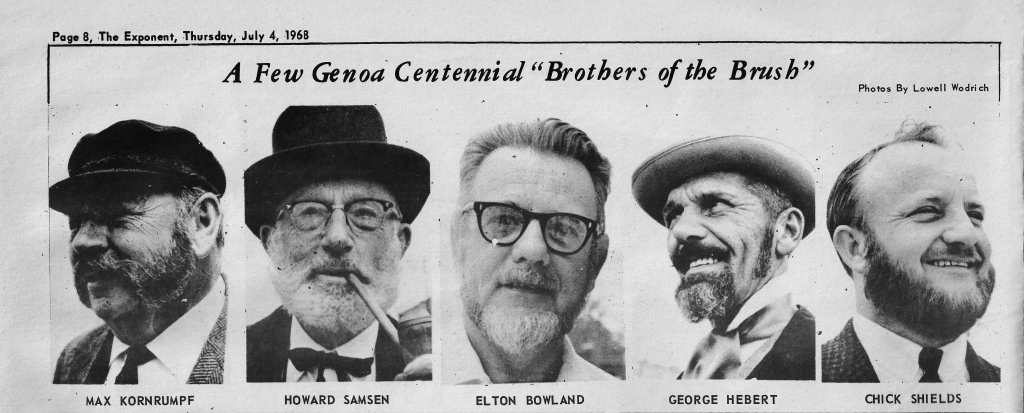

And speaking from my own experience as a Roger’s director, this seemed to be the essence of each celebration and each production. Every celebration would not only feature the pageant, but a “queen’s contest” which allowed local women in the town to sell tickets to the big show and the woman who sold the most won the crown and a truckload full of prizes from local merchants. Each celebration also featured beard growing contests for the men any man who grew some facial hair was encouraged to join the “Brothers of the Brush” which involved buying a button, an old-fashioned bow tie, and maybe a top hat or some other type of historic fashion.

The ladies, as well could pick through the racks of beautiful recreation of historic period dresses of many type which were at the Centennial store.

This store was also the headquarters for the event and was the place where everything was coordinated, meetings were and a variety of commemorative items were up for sale. Items that were mostly produced or brokered by the Rogers’ company. In fact the Rogers company also owned another firm called the Ohm Company which specialized in various trinkets, badges, hats and ties that most folks, who got into the celebratory spirit were eager to buy. It was a win-win-win situation. The town, the Rogers company and the director all shared a cut of the profits.

While money and the American “profit motive” were certainly in play for the Rogers Company, I always sensed that the owners and directors were motivated by more than just the almighty dollar, and that the greatest reward was in the sense of community these productions created. In the smaller towns across the country who got caught up in the spirit of the celebration, the people who took part often found themselves making new friends, sharing new experiences and generally painting some indelible memories they carried for many years.

One case in point, was my first show I directed on my own which was in Newell, Iowa. A small farming hamlet of 700 citizens in Northwest Iowa, not far from Storm Lake, and about 60 miles east of Sioux City. It was essentially in the middle of nowhere and I thought I’d be dealing with some pretty dusty folks who had corn silk in their ears. How wrong I was. This little town was as prosperus and progressive as any town I had ever known, and . the townspeople of this bucolic village were as energetic and friendly and competent as any I have ever encountered throughout the rest of my life. These folks knew how to have fun. A small town with a big heart. I learned a lot from them and never forgot their hospitality and zest for life. The show and the celebration of the town’s 100th birthday was a grand success. I was proud to be a part of it. In 2004, 35 years after the 1969 Newell Iowa Centennial. I decided to visit that small town again while on a trip out West. The intervening years had taken their toll. Much of Newell had physically changed, with closed up store fronts, and fewer downtown businesses. But more importantly, the people had not changed. Many of the same folks instrumental in putting the celebration together were still there, 35 years older, but just as eager as ever to have a good time. They held a party for me and my family. I was humbled. We reminisced, we laughed, we drank, we traded stories, and we paid tribute to those who had passed on, and by the night’s end, we made the past come alive again. I also realized that the Centennial they observed in 1969 was more than just a one week event. It had stayed with them for decades. Several told me that it was the biggest thing that had ever happened in their little town and it was a very important time in their lives. One they would never forget. Nor shall I.

The work of the Rogers Company may be over, but still quietly lives on in thousands of towns across America.

The Rogers Room At The Fostoria Museum