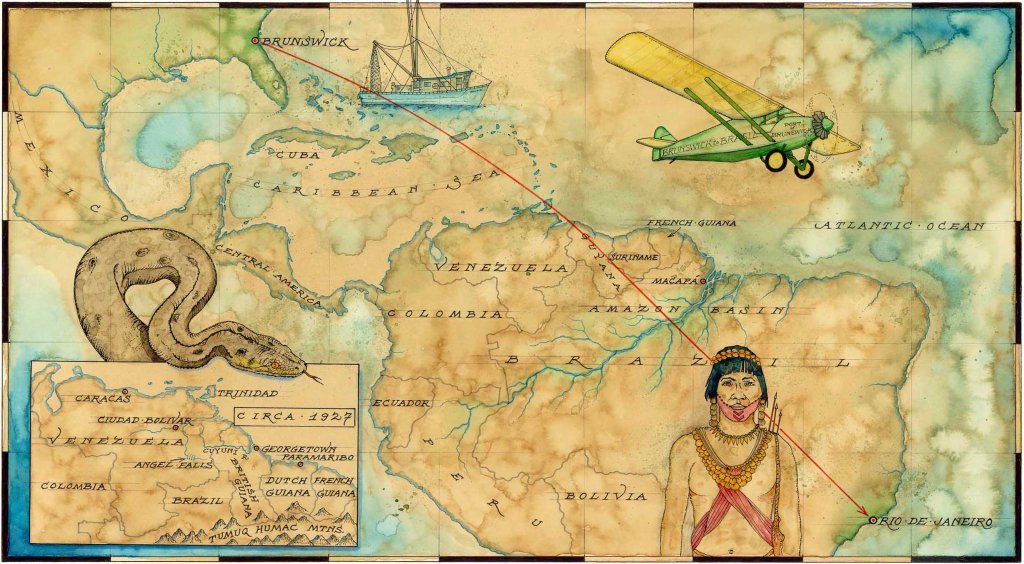

It will be 97 years this summer since the world last heard from Paul Rinaldo Redfern. The dashing young aviator was trying to make history as the first pilot ever to fly nonstop from the North America to South America. Tragically, he did make history, but not the kind he was seeking. Paul Redfern and his Stinson single engine plane vanished into the fog of mystery after he departed an airport in Brunswick Georgia that summer morning of 1927, leaving a behind him, a cheering crowd of well wishers and his worried bride from Toledo. In days to come, the only signs of him came from some reports that Redfern had indeed made it across the Carribean Sea and was spotted just off the coast of Venezuala when he flew low over some Norwegian fishing boats, and dropped some notes, while on a heading towards the mainland. What happened after that brief sighting? Over the next weeks, months and decades, his fate would become the subject of mystery, conjecture, hoaxes, sightings, hope and intrigue. Some say he made it to land, only to crash in the jungle and was severely injured, then taken captive by aboriginal natives in the rainforest. Some say they found pieces of his aircraft, and pieces of his clothing. Others claim there were reports of him taking a wife among the native tribes and having a child. In the end. No one knows for sure. His fate remains as mysterious as other ambition seeking aviators of the day who dared to defy the odds, only to become the stuff of legends.

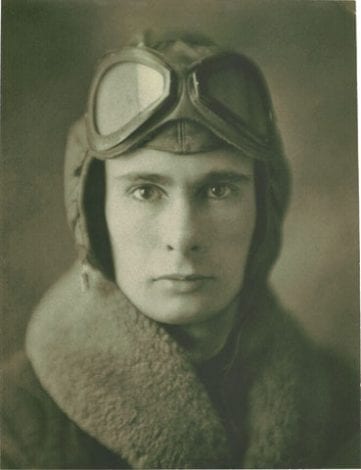

Who was Paul Redfern and what was his connection to Toledo? To answer the first part of the question; Redfern was a dreamer. An ambitious dreamer. Son of a preacher and educator. His full name was Paul Rinaldo Redfern. Born in 1902 to Blanche and Dr. Frederick Redfern. While raised for part of his life in New York and Ohio, he spent his teenage years in in South Carolina where his father was a dean at Benedict College. His mother taught English at Benedict. As a child, Paul would show great promise and intellect. He was said to be musical prodigy, his father wrote of him:

At an early age, Paul showed a strong mechanical inclination. His fascination with the violin led him to create one from a cigar box and a single string. He displayed exceptional musical ability by playing any tune that interested him. His unique technique involved holding the cigar-box fiddle between his knees and the staff against his shoulder. By age eleven, his exceptional playing caught the attention of the Idaho press, which featured his achievement and published his picture in a playing position.

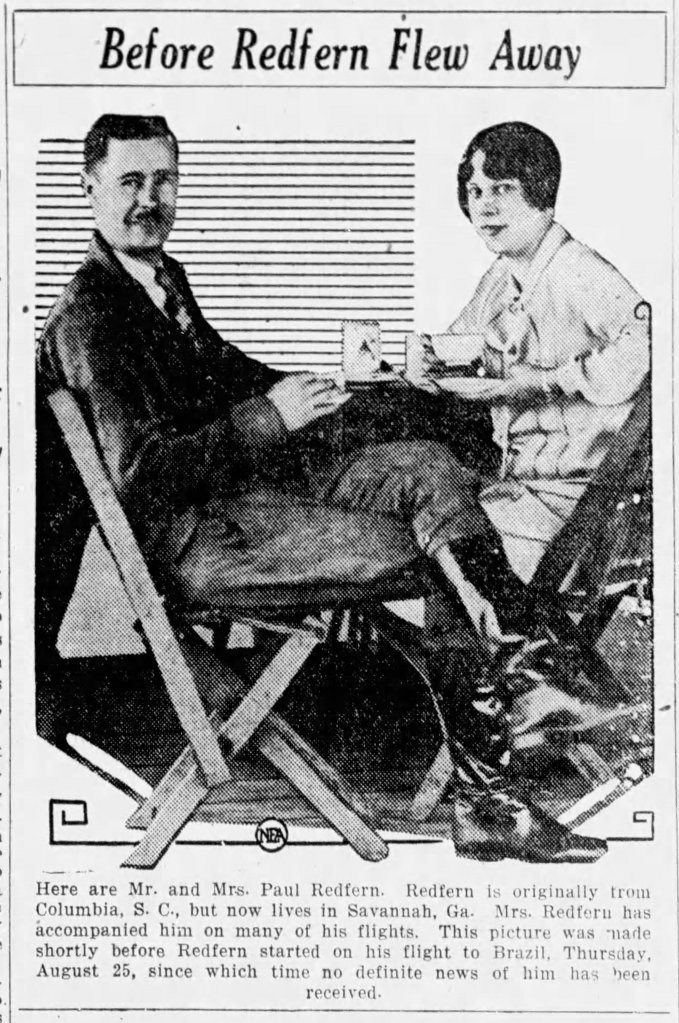

But Paul also had an keen mind for mechanics. He had so much natural talent in the understanding of the science and mechanics of aviation, that as a teenager, he built several small planes and gliders. At 16 years of age, he was asked by the U.S. Army to be a production inspector for their aircraft plant in New Jersey. He stayed with them until 1919. After the World War was over, he returned to South Carolina and finished high school. He build several more airplanes and after he graduated from high school, Paul acquired and flew a Curtiss Jenny JN-4 and a Dehavilland DH-4. It was then he began to realize his boyhood dream of making a living in the cockpit of an airplane. Operating out of the airport in Columbia, South Carolina, Paul started performing acrobatic stunts at county fairs, and became an “aerial advertising artist.” In addition to being a barnstormer, later he would work for the U.S. Customs office in spotting illegal whiskey stills from the air during prohibition. He also began to pioneer the first commercial flights, taking passengers to points North. Canada, New York and Ohio . It is not documented as what took him to Toledo, but by 1925, he had taken up residence in the Glass Cityand likely spent some time with other famous members of this pioneer flying fraternity in Toledo, such as Lincoln Beachey and the great Roy Knabenshue. It is in Toledo where he also flew promotional flights for numerous products, including a cigar company working for cigar salesman, Charles Hillebrand. Redfern’s job was to drop packages of the cigar samples around the city. As the story goes, Hillbrand and his wife invited the young fier over to their home for dinner and that’s when he met their daughter Gertrude. He fell in love at first sight with the pretty auburn haired 20 year old. The attraction was mutual. It didn’t take long for the two of them to begin a relationship and soon, they were married ny January of 1925. They lived for awhile in Toledo, but Paul was offered a job in Georgia and they moved from Toledo to Savannah where he got his job with U.S. customs as a flying revenue agent, finding illegal stills from the air.

Redfern obviously loved challenges and with the arrogance of youth, he jumped at the chance to accept a challenge to become the first pilot to fly solo from North to South American, non stop. The year was 1927. Lindberg had just made history flying from the US to Paris. Redfern wanted to break that distance record for a solo flight and this would be that opportunity. It would be a 4600 mile flight and would require at least two-days of being fully awake at the controls. The City of Brunswick Georgia said they would pay 25,000 to the first pilot who could achieve the feat and fly from their nearby airport on Sea Island Beach. It was the same amout that Charles Lindberg had earned just, a few months before. Redfern was certain he could do the same and more.

Barriers to Reaching Brazil

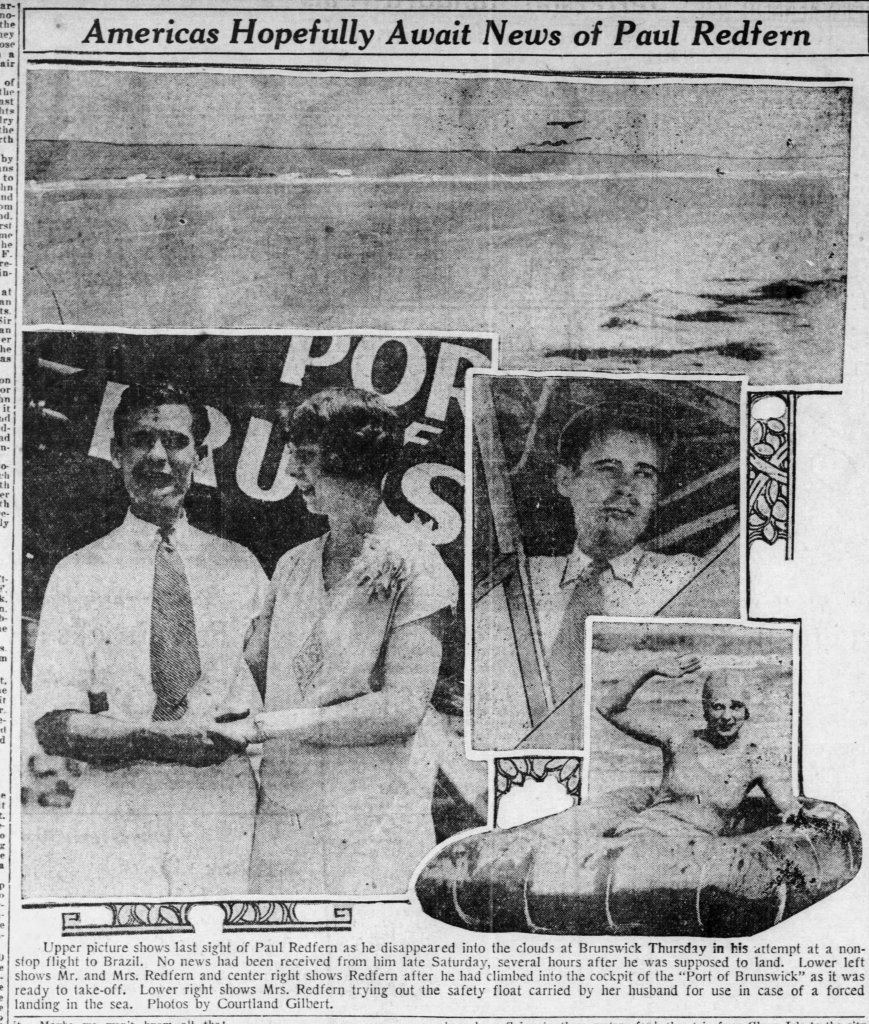

On Wednesday morning, August 25, 1927, Paul Redfern and his wife Gertrude appeared at Sea Island to greet the thousands of well wishers, photographers and reporters who gathered to see him this attempt to set a new long distance flight record. His green and yellow Stinson SM-1 Detroiter monoplane that he purchased from his friend Eddie Stinson in Detroit had been christened “Port of Brunswick”. The signs around the airport exclaimed “Brazil or Bust”.

The arduous journey by air would take him over the Atlantic Ocean and the Carribean and then over the tangled and dangerous jungles of the Amazon rainforest before reaching his destination of Rio De Janeiro. No shortages of hazards were involved.

The daunting itinerary provoked many questions. Could the plane stay aloft for those long hours of operations? Could Redfern stay awake? Even Lindberg admitted that he kept falling asleep on his transAtlantic flight to Paris. If he did crash in the jungle, would he survive? Or would he fall victim to the dangerous animals reptiles, and the hostile natives who inhabited the remote area? Redfern did bring some guns and a rifle with them for that possibility. He even packed some fishing gear and flares. He was undeterred and determined to break Lindberg’s distance record. If he did, he would eclipse that record by a thousand miles. And like Lindberg, in these early days of aviation, there was radio or altimeter or other modern avionics to help navigate. All he had was a compass and a map and a dream. And hopefully enough fuel.

He tried to allay the fears of friends and fears by saying he thought if he should have to crash land in the jungle he could still survive and someday emerge and not to give up on him “if you don’t hear from me maybe for weeks or months”.

Paul Redfern, Bound for Brazil

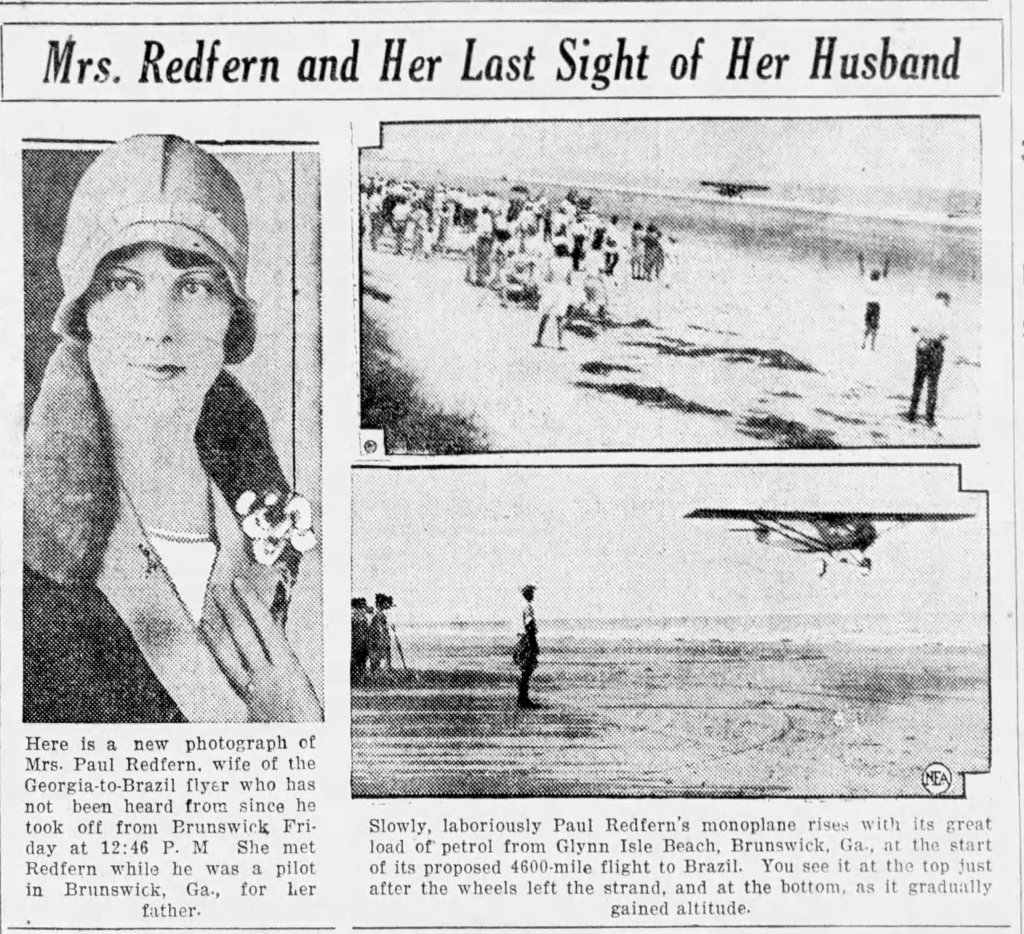

Paul’s take off from the beach airport in Georgia was officially recorded 12:46 p.m. He taxied the airplane down the beach and then as wife watched with a cheerful smile, the Stinson Detroiter slowly lifted above the horizon and then turned towards the sea on its way to South America. The crowd watched intensely as the planee droned over the water and out of sight. It was written by one reporter that his new Toledo bride, Gertrude Redfern watched tearfully and collapsed into the arms of a friend. Reality was upon her. Her beloved husband, Paul Redfern, was out of her embrace and out of her sight and she didn’t know if she would ever see him again.

The cheerful smile fell from her face and she couldn’t hold back her emotion and sobs. Paul soared over the Atlantic Ocean, heading southeast at 85 miles an hour. He managed to survive the first night in the air and the next morning off the coast of South America he saw a ship below him in the ocean. It was the Norwegian tramp steamer Christian Krohg. He dropped his altitude and descended to the ship and threw package with a note asking for directions to South America. The steamer captain pointed the bow Westward. According to this account, Redfern apparently had succeeded in traversing the miles over the ocean. Then later that day, Lee Dennison, an American engineer, reported seeing his plane, The Port of Brunswick, flying over Venezuela’s Ciudad Bolivar Plaza. But it was not a jubilant sighting. He said the plane was “trailing a thin wisp of black smoke.” If that indeed was Redfern plane, it was the last time it was seen.

Paul Redfern Vanishes

As Redfern was to wing his way south to Rio De Janeiro, hundreds of Brazilians were ready to great him at the airport and carry him into the city. Those in the waiting crowd were Washington Luis, President of Brazil, and Clara Bow, silent movie star. His plan was to drop some flares over the town of Macapa to signal whether or would make it to Rio or try to land at at the alternate site of Pernambuco. It would depend on weather and fuel supply.

As the hours dragged on, however, there were no flares sighted. No flares, nor any sign from the intrepid flier as thousands of people scanned the skies. watching and waiting. With no sighting that third evening, it was apparent that he either had run out of fuel and crashed, or had been forced to make a landing along a 2,500 mile route that stretched from the jungles of the Amazon to the mountains. Over the next days, the world was on edge awaiting some word from Redfern that he was okay. His wife, Gertrude was thrilled with the early story that he had been seen over Venezuela and believed at that time that her husband was safe, wherever, he may be.

Searching for Paul Redfern and the Port of Brunswick

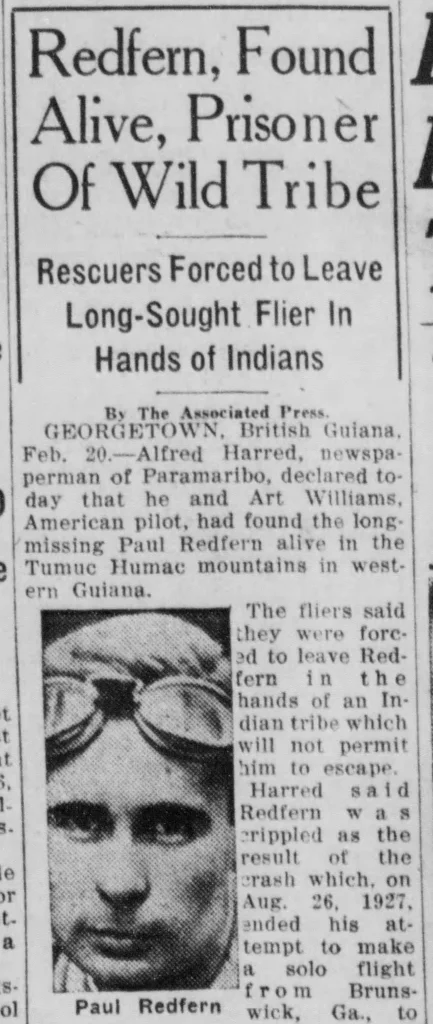

The long days though would turn to long weeks, and the hope would turn to resignation that Redfern’s fate was dubious at best. Over the next ten years, Paul’s family, including his wife, all traveled to the remote area of Brazil in search expeditions to see if they could find some shred of evidence or a clue to provide more information of his whereabouts and whether he was dead or alive. Every now and then, this void of information was filled by bush pilots or missionaries who would come forward with stories that he was seen alive. That he had crash landed and stranded in the jungle. In 1932, an American engineer named Charles Hasler made headline when he claimed that Indian natives were holding an American pilot whose legs had been broken, but the information was so limited that no expedition was organized.

In 1935, another story emerged of a “white man who came out of the sky, had both legs broken, and lived in an Indian village”. Similar accounts surfaced from jungle inhabitants in remote villages. Rescue and search parties formed, but after weeks of exploration, nothing was ever found. Rumors persisted.

The Searches Continue and Hope Lingers

Pilot Art Williams, in British Guiana, reported that in early 1936, that he passed over an Indian village in Brazil and that the Indians fled into the jungle but he saw “a lone white man standing in the open and waving frantically to the plane.” Williams said he later took a friend and they went back to the area with a small boat in an effort, but says when they finaly got to the village, a heavily armed tribe of Indians met them and they narrowly escaped with their lives.

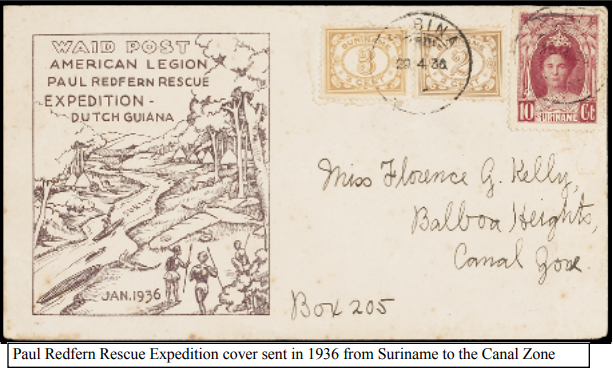

Another expedition was launched the next year in February 1936, when an American Legion Post in the Panama Canal Zone put together an attempt to find Redfern. CBSNews correspondent James A. Ryan also accompanied the expedition. To pay the trip, the group issued five thousand “Redfern Rescue” stamp covers that had postmarked from Dutch Guiana to sell to stamp collectors. One customer, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who bought two of the “Redfern Rescue” covers.

The search effort not only failed but ended in disaster and one man emerged from the jugle to report they found trace of Redfern and that CBS correspondent James Ryan had drowned when his canoe tipped over in a river.

Wife and Family Suffer From Cruel Hoax

There were more than a dozen search efforts made to find the lost pilot, but none to cold a cruel and the one in 1936 that fanned new hope that Redfern may indeed be alive and living as “white god” among a tribe of natives. It turned out to be nothing more than a despicable hoax.

Alfred Harred, a freelance reporter said he and the former pilot Art William actually found Redfern on in area on the Brazilain border with French Guiana. They said Redfern was living with a tribe of nude Indians and was hobbling around on crutches. His airplane was still hanging in the branches of a big tree.

He says Paul Redfern told them that when he crashed the plane, his legs and arms were broken, but eventually healed and married an Indian woman. He says they had a son. Harred claims that he and Art Williams were chased away from the village because the tribe thought they were going to take Paul redfern away. They fled under the threat of poison arrows and violence. This fantastic story as related by Alfred Harred were spread quickly around the world, it fell apart like a cheap suit in the rain. When reporters tried to contact Art Williams, he denied everything saying he never met Redfern and never met Alred Harred who would eventually admit it was all fiction.

The Final Rescue and Search Attempt

By the fall of 1937, there was yet another massive search effort underway to find yet another missing aviator. The object of this search: Amelia Earhart who vanished in her Lockheed Model 10 Electra in July of that year. As the world trained its attention on a remote island in the south Pacific where her plane was last heard from on a round the world attempt, the Redfern story seemed to fall to the margins. The world’s press was not as interested it seemed and Redfern’s fate was fading from the newsprint.

That however did not deter Paul Redfern’s family in their quest to get some answers. Ten years had passed but they wanted to try one more time to find their son and Gertrude’s husband. In 1937, they requested New York explorer Theodore J. Waldeck to lead an expedition from British Guiana. This attempt was risky and deadly. The expedition became marooned at a place called Devil’s Hole on the remote Cuyuni River . One of the men on the trip, Dr. Frederick Fox of New York, contracted jungle fever and died. He was buried on site as the others kept travelling until April 27, 1938. On that day, Theodore Waldeck reported that he had found the wreckage of the Port of New Brunswick in Venezuela. He says he could prove that Paul Redfern was in fact dead, but for some reason he never did. So as far as many were concerned, the young aviator’s fate was still unknown. His parents never gave up hoping that someday he might walk out the jungle and walk back into their lives.

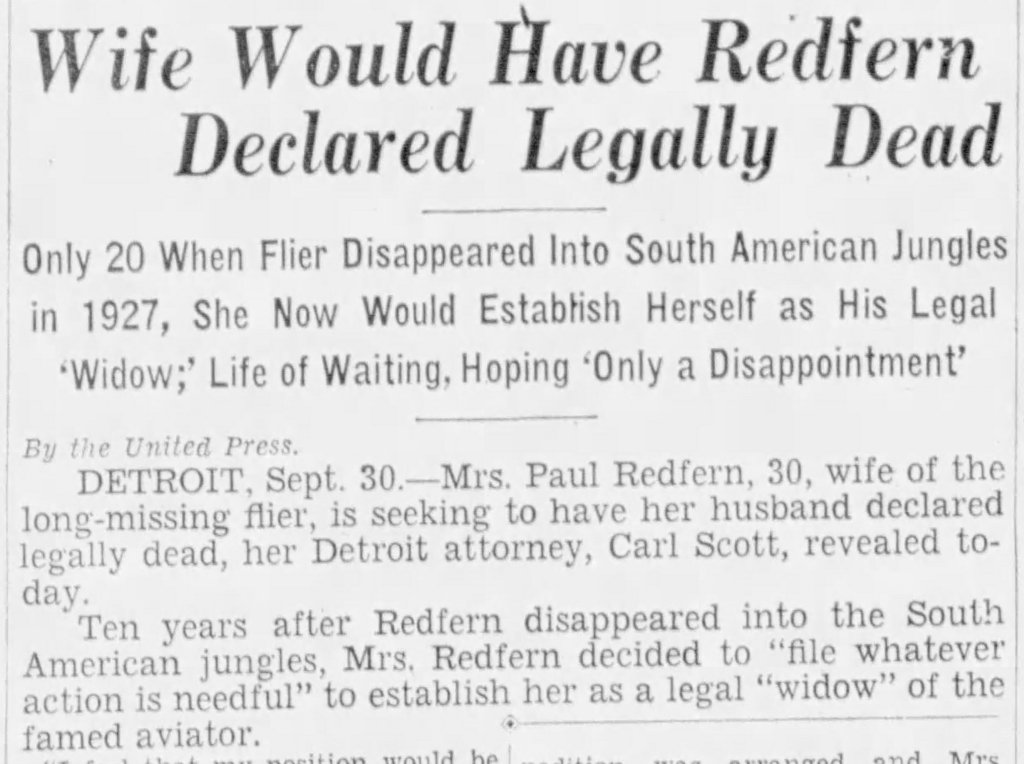

His wife Gertrude also held on to hope for many years, but finally, after she too had gone to South America on one of the many expeditions, she also became more convinced that his fate was tragic, and decided it was best to move on with her life, as best she could. While living and working in Detroit, she petitioned a Michigan court to have her husband declared legally deceased. They had no children, and Gertrude never remarried. The Toledo native lived the balance of her life as a single widow and and died in 1981.

.The story of Paul and Gertrude Redfern is hardly recorded in Toledo. More so in Redfern’s South Carolina. At the time, as the drama was unfolding, the Toledo papers heavily covered this local-interest real life adventure mystery. But news stories do have a limited “shelf life”, even one as compelling as this. When Gertrude Redfern passed away in 1981, there was no significant story in the Blade’s obituary, but just a mere mention of the fact of her dead pilot husband’s disappearnce in South America. The story had lost its luster with each passing decade along with the generations of Toledoans who might have followed its many twists and turns.

But Redfern’s tale has been given some new lift in recent years. The world it seems loves a good mystery and this is surely one of them. Will we ever really know what happened? And could there have been a seed of truth in all the reports that he in fact did crash and survived. There are many who still believe the end of the Redfern tale did not end with a fatal plane crash. And that he may have survived. There are others who think he may have veered far off course and the searchers were all loooking in the wrong place. Whatever and wherever his fate, Redfern’s name is now a legend. At Rio de Janiero, there is even a street named for him. Back at home, in South Carolina, his high school in Columbia bears a plaque and a sign in his memory, as does the airfield in Brunswick, Georgia. In South Carolina there is a group called the Paul Rinaldo Redfern Aviation Society. The group reportedly meets every August 25th, at exactly 12:46 p.m., the exact time that Redfern’s Stinson Detroiter, called the “Port of Brunswick” crawled down the runway, lifted into the blue and disappeared over the horizon on that summer morning in 1927. At that appointed time they hold a ceremony and they raise a glass, maybe more, to this one-time Toledo aviation pioneer, wherever he may be.